The Threat of Mandatory “Enhanced ID” for Air Travel

Originally published by The Kennedy Beacon.

Following an unprecedented series of revelations about the collusion of Big Tech and government agencies in monitoring and censoring Americans, the issue of digital privacy and autonomy is high on the priority list for 2024 voters. As recently highlighted by independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., even our cars have become tools of surveillance and data collection, placing unprecedented control over our most sensitive personal information in the hands of a few.

At the same time, however, the issues of border security and election integrity are increasingly top of mind for voters – particularly those in border states such as California, Arizona, and Texas. This amalgam of issues has led to numerous proposed solutions, such as RFK Jr.’s plan to make federal passport cards available for free to every American who wants one. As we previously covered in The Kennedy Beacon, these passport cards would serve as suitable identification for domestic air travel and voting, as well as help mitigate aspects of illegal immigration across the border. Most importantly, his proposal does not call for such IDs to be mandatory – rather, to serve as the best choice out of the available options for the president of the United States. However, one issue that remains unresolved is how easily accessible ID cards reconcile with ever-increasing concerns of data privacy, and the threat of intrusive programs along the lines of “vaccine passports.”

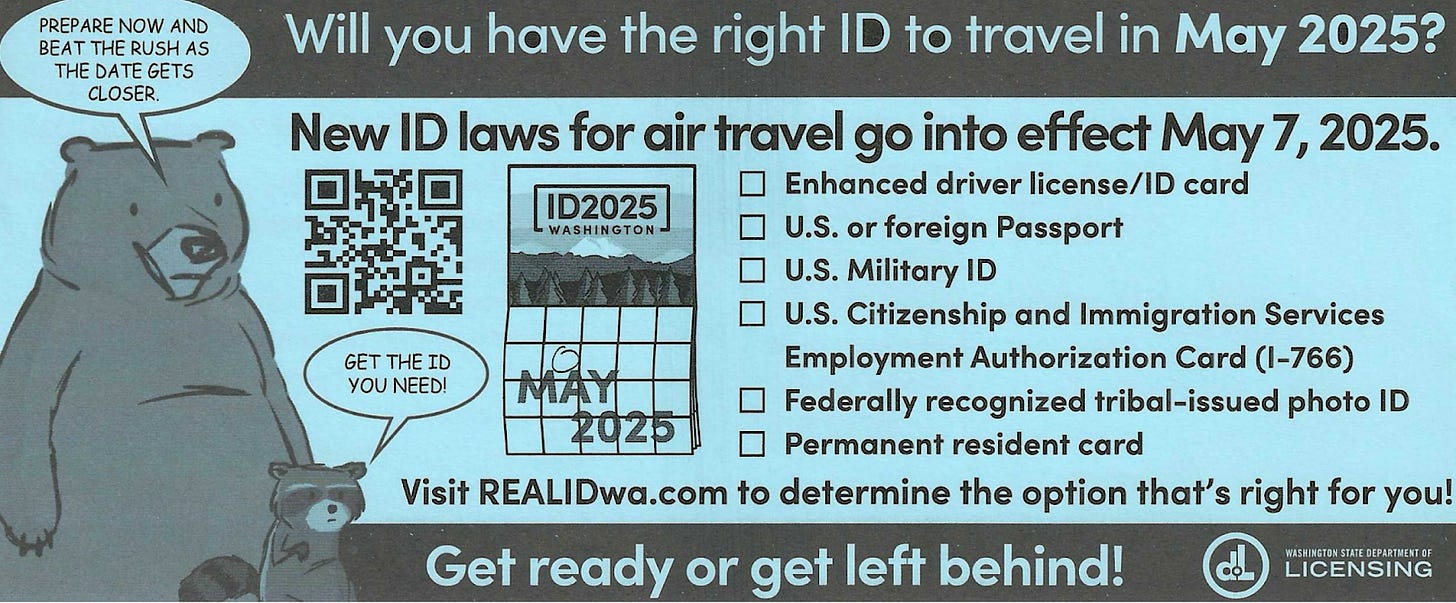

In the days following Christmas, residents of Washington state were notified that new ID laws would soon be going into effect. As of May 7, 2025, the paper notice read, air travelers will be required to present identification that is “REAL ID” compatible. “Get ready or get left behind!”

What is “REAL ID,” and why is the Washington State Department of Licensing warning residents to get one with such urgency?

REAL ID Act of 2005

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. Congress passed the REAL ID Act of 2005. This was based on the recommendation of the 9/11 Commission, which argued that the alleged terrorist hijackers were able to bypass existing security measures by forging identification documents. To resolve this, the Commission recommended in its report that the federal government “set standards for the issuance of birth certificates and sources of identification, such as drivers licenses.”

While this sounds like a commonsense idea in theory, its implementation is another matter. As explained by Democracy Now! in an article published just days prior to the 2005 passage of the REAL ID Act, the bill was sent to the Senate by the House of Representatives “as part of a ‘must-pass’ appropriations measure for troops in Iraq and tsunami relief.” The bill was quickly passed by Congress without either chamber having held “hearings or thorough discussions on the measure.” Two years later, Senator Patrick Leahy, a Democrat, issued a statement describing REAL ID as “an issue of great concern to many States, and to Americans who value their privacy in the face of the Federal government’s expanding role in their daily lives.” The legislation was established before anybody understood what exactly it meant, leaving the public and government officials alike with far more questions than answers.

Long List of Concerns

While the ambiguous new regulations were originally scheduled to take effect in 2008, the program has been met with heavy resistance from “hundreds of civil liberties groups, immigrant support groups and government associations,” as WIRED reported at the time. Some liberal activists focused on the implications for immigrants and asylum seekers, whose prospects of safely remaining in the United States would be significantly diminished once the bill comes into effect. For state agencies, the concerns stemmed from the inevitable bureaucratic burden on their local offices, as well as the millions of dollars estimated to be required to implement the new policies.

But for the individual American, the greatest risk was always to privacy. In order to be REAL ID compliant, states would be required to issue driver’s licenses and ID cards capable of storing machine readable data. At the time the bill was passed, it didn’t specify what technology would be used in order to meet this requirement – or which data states would be required to collect and store on the ID card. Regardless, the idea was for the data on these cards to be checked against a federal database anytime somebody checked into a flight or engaged with the federal government (such as accessing social security benefits, or entering certain federally controlled facilities).

Deadlines and Delays

As a result of the many concerns raised, the implementation of the REAL ID Act has repeatedly been delayed, accompanied by further warnings of a deadline that never passes. In the meantime, the Department of Homeland Security has continued to prepare for the Act’s eventual enforcement. This has provided time for both technological advancement and administrative capacity to develop, inching REAL ID closer to reality behind the scenes.

In a September 2020 study published in Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Wingate University’s Magdalena Krajewska explains how DHS officials fostered direct working relationships with local offices of the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), through which the agency progressively assuaged the bureaucratic and financial concerns of the staff across the country who will be responsible for the bulk of the work. “Instead of focusing on state governors and legislatures that were often critical of REAL ID,” she writes, “the REAL ID Program Office focused on working directly with state Department of Motor Vehicles (DMVs) to implement the REAL ID standards.”

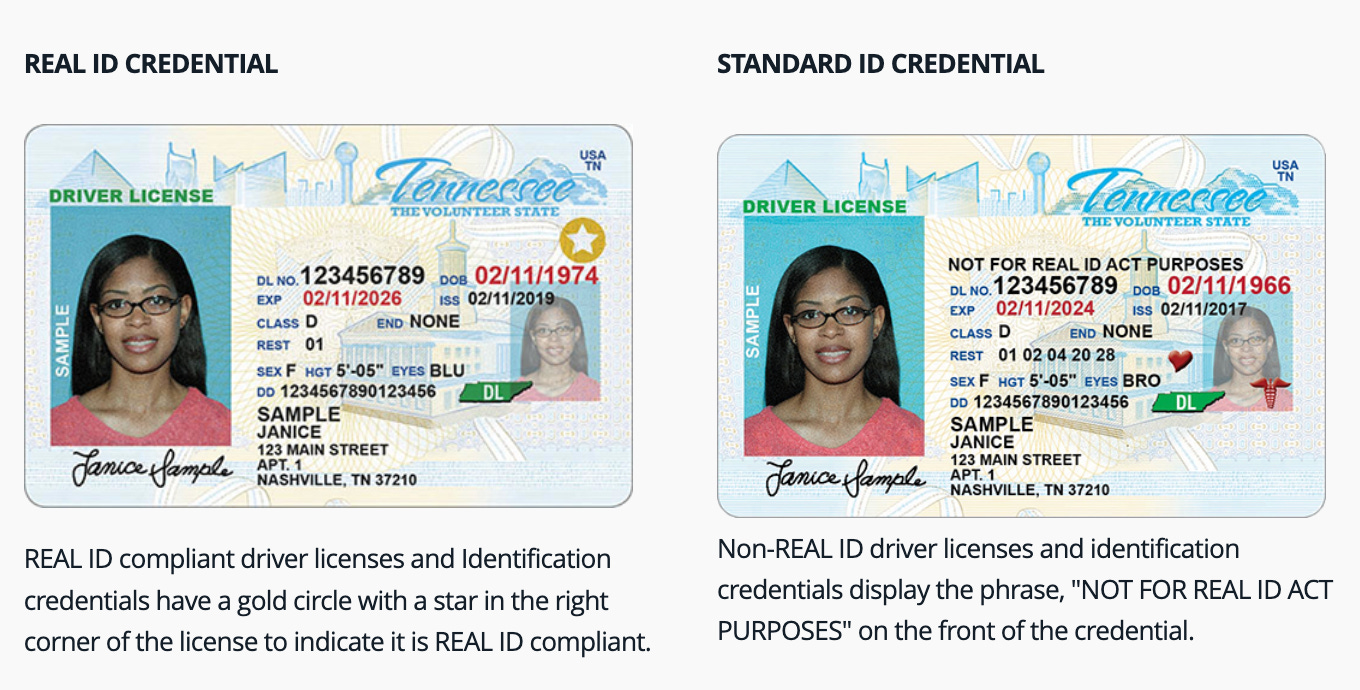

Indeed, the technology available in 2024 far exceeds what was around in 2005, and much of the transition to REAL ID compliant ID cards has already taken place. A glance at the samples provided on the website of the Tennessee Department of Safety & Homeland Security shows two virtually identical cards, one bearing a gold star and one without – a minute difference for something so consequential.

The same can be said for the Washington state website. In addition to the paper flier campaign, the Washington State Department of Licensing hosts a website called ID2025, which offers an interactive tool to determine if residents already have compliant ID, or need to apply for a new one. For example, anybody who has a passport card is “good to go,” as per the tool. Those who only hold a regular driver’s license, however, are required to upgrade to the so-called “enhanced” license.

As described on the Department of Licensing website, “enhanced” licenses are equipped with a radio frequency identification (RFID) tag, ostensibly intended to “speed [up] identification checks at border crossings.” This means that the card sends and receives information based on proximity. According to a document published by the State’s Department of Licensing in November 2022, RFID tags are required by the federal government under the REAL ID Act. Alarmingly, the Department of Homeland Security confirms that the RFID chip embedded in enhanced driver’s licenses “will signal a secure system to pull up your biographic and biometric data for the CBP [Customs and Border Patrol] officer as you approach the border inspection booth.”

In a report published by DHS in December 2006 (after the REAL ID Act had already passed through Congress), the use of RFID chips in ID cards is described as having notable risks, including in the context of their intended use at border crossings. In addition to being susceptible to unauthorized access of the data held on the card, DHS notes a “concern that the information produced by an RFID‐enabled credential system for a stated purpose might be reused or leveraged for a second purpose without the knowledge or consent of those persons whose information was collected for the original purpose.” But most importantly, the DHS report acknowledges the downside of the “selection of RFID‐enabled systems for an application if other existing and potentially less privacy‐impacting alternatives can achieve the same benefit.”

In an era where governments and corporations around the world are aggressively pushing for the mass rollout of digital ID systems with wide-reaching privacy and human rights implications, it is worth examining whether these high-tech measures are actually intended to bolster the security of the American people. As noted by ACLU senior policy analyst Jay Stanley, the REAL ID system “is threatening to prematurely lock in a harmful digital identity system that allows ID card issuers to track where people show their ID, fails to include a number of important privacy protections, and fails to ensure that the system is free from the control of particular private corporations.” There seems to be no gain and all risk with this level of technological immersion, offering no reasonable prospect of combating identity fraud while removing any semblance of free movement left within America.

Americans are now faced with the difficult task of choosing whether to accept the new status quo, or to seek reform of the REAL ID Act in order to best accomplish the goals for which it was ostensibly conceived.

Liam Sturgess is an investigative reporter for The Kennedy Beacon. He is also a writer for the Canadian Covid Care Alliance and founder of Sturgess Prime Productions. He was the founding co-host and producer of the Rounding the Earth podcast, and publishes a Substack series called Microjourneys.